Uncovering Hidden Diversity: A Collaborative Fungi Survey at Pulai Trail

Received: 9 December 2024 / Accepted: 22

Feb 2025

pulai@freetreesociety.org

Abstract Fungi are of great importance in both ecology and economy. A mycological survey was conducted at Pulai Trail Community Forest to document its fungi diversity on the 17th and 24th of November 2024 by a group of experts and enthusiasts organized by the Malaysian Nature Society Selangor Branch Mycology Special Interest Group (MNSSB Mycology SIG) and the Free Tree Society. The observations were uploaded and documented to the iNaturalist platform, namely the Pulai Trail MycoBlitz project. The data showed that the fungi and other species found could benefit local communities that call Pulai Trail home when more comprehensive studies are conducted.

Introduction

Pulai Trail Community

Forest (Pulai Trail) is 6 hectares of forested wilderness in Bukit Persekutuan,

Kuala Lumpur. It is one of the last remaining green spaces in the metropolis,

hidden with biodiversity waiting to be explored. To date, there is no comprehensive

mycological survey in the area, and therefore, its fungi diversity is yet to be

known.

On November 17th and

24th, 2024, the Malaysian Nature Society Selangor Branch Mycology Special

Interest Group (MNSSB Mycology Group) conducted a two-day fungi survey at the

forest with trail guidance from the Free Tree Society. The survey was led by

Loon Yit Hong and five members that consisted of fungi enthusiasts and citizen

scientists. The team explored the main access trails, Pulai Loop 1 and 2

Trails, which covered a total distance of 1.2 kilometers.

The survey aims to document the fungal diversity in the forest and understand its ecology and economic value, which may benefit local communities in Bukit Persekutuan.

Pulai Trail Mycology Survey Team: MNSSB Mycology Group Leader Loon Yit Hong (2nd from the right),

President of the Free Tree Society, Madam Carolyn Lau (3rd from the right) and volunteers.

Material

and Method

Survey Area and Data Collection

The survey area was

conducted along the main access trails, Pulai Loop 1 and Pulai Loop 2. The

two-day survey was conducted on November 17th and 24th, 2024, for two

consecutive weeks during the wet rainy season in Selangor, Peninsular Malaysia.

Information about the fungi (including identification, photos, coordinates, size measurements, description, and ecology) was documented and uploaded to the iNaturalist platform, namely the Pulai Trail Mycoblitz project. Further accurate identification is verified by mycologist1 and expert2.

Results

and Discussions

Despite surveying the

area in a limited period of time, we made 172 observations and confidently

recorded 54 different species of fungi, with more still to be identified.

Pulai Trail Survey Map with observations indicated in the iNaturalist project, Pulai Trail Mycoblitz.

Before our survey,

Pulai Trail had only 43 observations of fungi on the iNaturalist platform (https://www.inaturalist.org/projects/pulai-trail-mycoblitz),

representing 18 species from 13 observers. Thanks to our group’s efforts, this

number has now grown to 203 observations and 51 species (with many more still

to be uploaded). The findings from this survey provide a snapshot of the incredible

fungal diversity at Pulai Trail.

Survey Summary: 172 observations with

50 species of Fungi and 4 species of Protozoans are recorded.

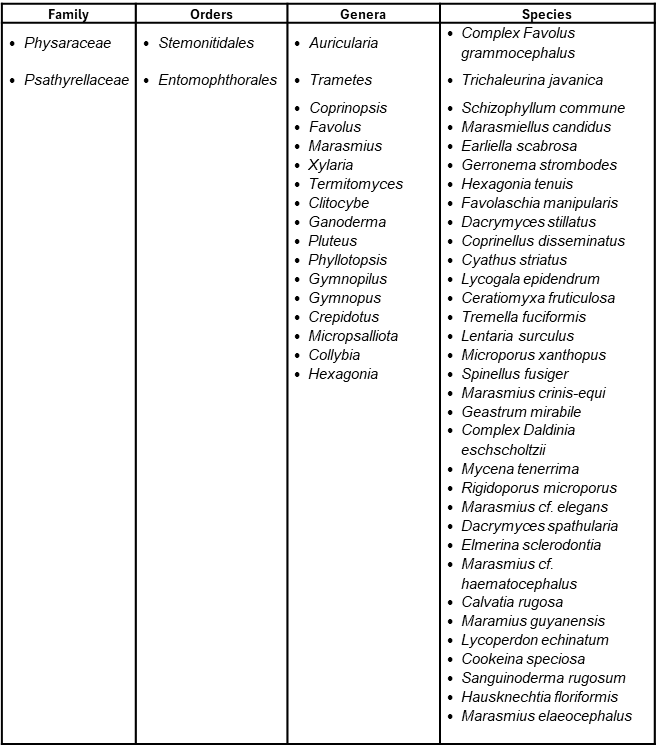

Recorded Families, Genera, and Species

Our findings encompass a wide range of fungal families and genera as summarized in the following table.

Survey Summary: List of Recorded

Families, Orders, Genera, and Species.

Ethnomycology of Pulai Trail Fungi

Ethnomycology bridges

cultural practices and the ecological significance of fungi, illustrating their

roles in local traditions, cuisine, and medicine. Below, we explore the

cultural and ethnomycological relevance of key fungi identified during the

Pulai Trail survey.

Trichaleurina javanica (Elephant’s Foot)

In different parts of

Malaysia, it carries a variety of local names. In Sabah, it is referred to as

"Mata Rusa" (deer eyes) by the Dusun people, while in Sarawak, it is

known as "Mata Kerbau" (buffalo eyes). It is not only culturally significant

but also valued as a marketable species, where it is consumed and prized for

its unique texture and potential health benefits.

In Madagascar, T. javanica is known among the

Betsimisarakas people as "Ranomatonantibary," meaning "tears of

an old woman." The copious gel produced by this fungus has been

traditionally used to treat ophthalmia (inflammation of the eyes), showcasing

its ethnomedicinal significance (Iturriaga et al., 2021).

The diversity of names

and uses for T. javanica highlights

its cultural importance across regions. While it is not widely consumed in all

areas where it is found, its unique appearance, market value, and potential

health benefits suggest it has underexplored uses in both ethnomedicine and

mycological research. Its distribution and traditional applications make it a

notable species for further study, both for its ecological role and its

cultural value.

Schizophyllum commune (Splitgill Mushroom / Kulat Sisir)

● Cultural Importance: Schizophyllum commune is a cornerstone of Malaysian ethnomycology.

Known as "kulat sisir" (comb fungus), it is recognized for its

medicinal and culinary uses among various indigenous communities. Indigenous

groups such as the Jakun in Johor and Temuan in Selangor use it to treat

respiratory conditions and for its anti-aging properties (Ayu et al., 2019; Foo

et al., 2018; Samsudin & Abdullah, 2019).

● Medicinal Properties: Modern studies reveal

that S. commune contains

polysaccharides with immune-modulating effects, offering potential in cancer

therapy. It is also studied for its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory

properties (Samsudin & Abdullah, 2019).

● Economic Value: The fungus has potential as a

sustainable, low-cost source of protein and micronutrients, comparable to

commercial mushrooms. It is occasionally sold in local markets and used in

soups and stir-fries (Ayu et al., 2019; Foo et al., 2018; Samsudin & Abdullah,

2019).

Schizophyllum

commune /

Splitgill Mushroom (Kulat Sisir)

(Photos by: Khor Hong Beng)

Cookeina spp. (Cup Fungus)

● Cup fungi such as Cookeina spp. are referred to as

"kulat mangkuk" (bowl fungus) and are occasionally collected for

their bright, colorful appearance or as minor culinary items. Villagers in

Sabah and Sarawak reportedly use related species as garnish or in soups

(Abdullah & Rusea, 2009; Foo et al., 2018).

● Ecological Note: This species typically grows

on decaying wood in moist environments, highlighting its role in nutrient

cycling within forest ecosystems (Abdullah & Rusea, 2009).

Cookeina spp. / Cup Fungus

(Photos by: Jacqueline Low and Loon

Yit Hong)

Microporus xanthopus

● Medicinal Uses: This vibrant bracket fungus is

valued for its anti-aging properties among indigenous communities. The Jakun

people have used it as a remedy for breast cancer and birth control. Its

traditional applications highlight the need for biochemical studies to validate

these uses (Ayu et al., 2019; Foo et al., 2018).

● Aesthetic and Decorative Use: Beyond medicine,

its bright yellow hues make it a potential candidate for ornamental or artistic

purposes (Foo et al., 2018).

Microporus xanthopus (Photos by: Loon Yit Hong)

Ganoderma spp.

● Medicinal Significance: Although not recorded

directly in the Pulai Trail survey, Ganoderma

spp., particularly Ganoderma lucidum

(lingzhi), is integral to Malaysian ethnomedicine. Used in powdered or

decoction forms, it is reputed for anti-cancer, anti-tumor, and immune-boosting

properties (Foo et al., 2018; Samsudin & Abdullah, 2019).

● Cultural Connection: Revered in Chinese and

indigenous Malaysian traditions, Ganoderma

represents longevity and health, often consumed as herbal tea or supplement

(Foo et al., 2018).

Ganoderma sp. (Photos by: Jacqueline Low)

Auricularia sp. (Wood Ear Mushrooms)

● Culinary Staple: Known as "kulat

korong" in Malaysia, Auricularia

spp. is widely consumed, often in soups or stir-fries. Its gelatinous

texture and mild flavor make it versatile in Malaysian cuisine (Foo et al.,

2018; Samsudin & Abdullah, 2019).

● Medicinal Benefits: Wood ear mushrooms are

traditionally used to treat hypertension and improve cardiovascular health.

They contain bioactive compounds that aid in blood thinning and cholesterol

reduction (Samsudin & Abdullah, 2019).

Auricularia sp. / Wood Ear Mushrooms

(Photos by: Jacqueline Low)

Xylaria sp.

●

Traditional Uses: Known for its tough, woody

texture, Xylaria sp. is not typically

consumed but is valued in indigenous folklore for its unique morphology, which

resembles burnt matchsticks (Samsudin & Abdullah, 2019).

●

Ecological Insights: As a saprobe, it

decomposes deadwood, enriching the soil and promoting forest regeneration

(Samsudin & Abdullah, 2019).

Xylaria sp.

(Photos by: Loon Yit Hong)

Termitomyces spp.

The

genus Termitomyces R. Heim is a paleotropical and edible mushroom classified

under the family Lyophyllaceae (Basidiomycota). The genus forms an obligate

symbiotic or mutualistic association with the fungus-feeding termites.

In

Malaysia, Termitomyces spp. is locally known as “Cendawan busut”, “Cendawan

melukut”, “Cendawan susu pelanduk”, “Cendawan anai-anai”, “Cendawan guruh”,

“Kulat tahun”, “Cendawan Tali” or “Kulat Tahun” (Change et. al. 2004, Azlina

et. al. 2012, 2013). Species that have been reported found in Peninsular

Malaysia: Termitomyces clypeatus, T.

entolomoides, T. heimii, T. eurhizus, T. microcarpus, T. aurantiacus, T.

radicatus and T. striatus.

(Pegler et. al., 1994, Turnbull et. al., 1999, Siddiquee et al. 2015).

Recently, a new species was discovered in Sabah (Jaya Seelan et al., 2020).

Termitomyces sp.

(Photos by: Loon Yit Hong)

Tremella fuciformis (Snow Fungus

/ White Jelly Fungus)

Tremella fuciformis, commonly known as Snow Fungus or White Jelly Fungus, is reportedly consumed by the Sabah indigenous population. It is locally called “Kulat Jeli putih.” The information on culinary and wild mushroom practices was mostly received from elderly people and passed on to the younger generations (Foo et al., 2018).

It is one of the most studied mushrooms that are reported to have medicinal properties such as skin nourishment, anti-aging, cholesterol-lowering, neurological protection (Shahrajabian et al., 2017), anti-inflammatory (Sassy & Kwanchanok, 2024), and more.

The mushroom is also used in pharmaceutical and cosmetic applications (Sasikala et al., 2023). The researcher concluded that its extract is a potential candidate for skin whitening formulations and warrants further studies. This formulation is a safer alternative to synthetic whitening formulations due to the usage of fully natural ingredients.

Tremella

fuciformis (Snow

Fungus / White Jelly Fungus)

(Photos by: Loon Yit Hong)

Pathogenic and Parasitic Fungi of Pulai Trail

Fungi

Rigidoporus microporus

Rigidoporus microporus is a well-known fungal pathogen, causing white root disease on more

than 100 different tree species. The greatest loss caused by this pathogen was

recorded in rubber tree (Hevea

brasiliensis) plantations (Nandris et al., 1987). Pulai Trail is a former

rubber tree plantation and it is unsurprising to find the pathogenic fungi

during the survey. However, it is unknown if the disease started to infect

other non-rubber trees and caused harm to them. It is alarming that we have

found the pathogen is infecting some young trees on our survey.

It

is suggested that forestry experts do a more comprehensive survey to assess the

risk of tree mortality from the pathogenic diseases at Pulai Trail.

Rigidoporus

microporus on

an unknown tree host at Pulai Trail.

(Photos by: Loon Yit Hong)

Rigidoporus

microporus on

a young unknown tree host at Pulai Trail.

Risk assessment is required to

evaluate the pathogen infections on trees at the forest. (Photos by: Loon Yit Hong)

Spinellus fusiger (Bonnet Mold)

Spinellus fusiger is the most common and widespread of the parasitic fungi seen on Mycena (Bonnet mushrooms) found on

decaying wood or leaf litter in moist forests. The genus Mycena and many small

mushrooms with fragile caps and slender stems are perfect hosts for Spinellus fusiger, which exploits the

mushroom’s surface as a base for its reproductive structures (Patrick 2024).

This

parasitic relationship is fascinating because Spinellus does not typically kill the Mycena mushroom. Instead, it uses the mushroom as a stable surface

and nutrient source for producing its own spores. The Spinellus hyphae (fungal threads) penetrate the mushroom’s outer

tissue, drawing nutrients from it, and then grow into the characteristic

sporangia-bearing filaments that cover the mushroom cap and stem (Patrick

2024).

As

a result, the mushroom becomes a vessel for Spinellus

fusiger’s reproductive process, continuing its lifecycle by dispersing

spores across the forest floor, where they might land on other mushrooms and

begin the cycle again. While the Mycena

mushroom may appear decomposed or weakened by this interaction, it often

survives the parasitism long enough to complete its own reproductive cycle,

spreading its own spores as well (Patrick 2024).

Spinellus

fusiger on a Mycena sp. mushroom.

(Photos by: Loon Yit Hong)

Entomophthorales (Insect Destroyer)

The

Entomophthorales (Insect Destroyer)

are an order of mainly entomogenous fungi. They are usually associated with Diptera, although some are pathogens of

other arthropods, nematodes, and tardigrades, amongst others (Kirk & Voigt,

2014).

The

typical life cycle of the entomopathogenic species of Entomophthorales involves the invasion of the host by germ hyphae

produced by adhesive spores (conidia), which are airborne. The fungus invades

the abdomen of the host. Following its death, sporophores are produced,

typically between the individual segments of the abdomen, where a new crop of

forcibly discharged spores is produced. Resting bodies are often produced

within the host, and the primary conidia also have the ability to produce

typically smaller secondary conidia, usually of the same form or as

morphologically distinct microconidia (Kirk & Voigt, 2014).

Entomophthorales are studied as a potential biological control of pest insects in

agriculture (Barta & Cagáň, 2006). They are valuable agents to control the

specific insect population as most of the species are closely host-specific,

and they pose no threat to non-target organisms.

Entomophthorales on an ant host. (Photos by: Loon Yit Hong)

Ectomycorrhizal Fungi of Pulai Trail

Ectomycorrhizal fungi are a type of fungi that form a symbiotic

relationship with the roots of various plant species. This relationship is

important for the ecosystem because it helps plants absorb water and nutrients,

and the fungi obtain carbohydrates in return.

It is surprising that almost all the fungi found are ascomycetes

and basidiomycetes that are saprophytic and parasitic. These include

decomposers that grow on fallen trees, branches, and leaf litter. The largest

group of fungi that play an important role in organic matter decomposition and

nutrition recycling.

The ectomycorrhizal fungi that are not spotted in our survey could

be due to not entering their fruiting season yet. A long-term six-year study by

Lee et al. 2002 suggested that the fruiting peak season of the mycorrhizae is

in February-March and August-September. It could also be because the forest was

a former rubber plantation estate where the mycorrhizae required a longer time

period to establish.

This fact requires further study by our team.

Conclusions

Acknowledgement

Loon Yit Hong (Event Organizer and MNSSB Lead

Coordinator)

Carolyn Lau (President and General Manager of Free Tree Society)

1Luca Pilia

(Mycologist)

2Joseph

Pallante (Amateur Mycologist)

Malaysian Nature Society Selangor Branch (MNSSB)

Event volunteers: Jacqueline Low, Lenny Wong, Kho Wui Kiong, Khor Hong Beng,

and Chan Chee Keong.

Sponsor

Project Titled: “RUGS, Pulai Trail: Advocacy and Capacity Building for Urban Forest Protection”.

References

●

Abdullah, F., & Rusea, G.

(2009). Documentation of inherited knowledge on wild edible fungi from

Malaysia. Blumea - Biodiversity Evolution and Biogeography of Plants

54(1):35-38 DOI:10.3767/000651909X475996.

●

Ayu, K. K., et al. (2019).

Documentation of macrofungi traditionally used by Jakun people in Johor,

Malaysia. August 2019IOP Conference Series Earth and Environmental Science

269(1):012013. DOI:10.1088/1755-1315/269/1/012013.

●

Azliza MA, Ong HC, Vikineswary S,

et al. (2012). Ethnomedicinal resources used by the Temuan in Ulu Kuang

Village. Ethno-Med. 2012;6(1):17–22.

●

Azliza MA. (2013). A comparison of

ethnobiological knowledge between the Mah Meri and Temuan tribes in Selangor

[master’s thesis]. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya.

●

Chang YS, Lee SS. (2004).

Utilisation of macrofungi in Malaysia. Fungal Divers. 2004; 15:15–22.

●

Foo, S. F., et al. (2018).

Distribution and ethnomycological knowledge of wild edible mushrooms in Sabah.

Journal of Tropical Biology & Conservation (JTBC) 15: 203–222:203–222.

DOI:10.51200/jtbc.v15i0.1494.

●

Iturriaga, T., et al. (2021).

First collection of the asexual state of Trichaleurina javanica from nature and the placement of Kumanasamuha. Asian Journal of Mycology 4(1): 19–28. DOI:10.5943/ajom/4/1/3.

●

Jaya Seelan et al. (2020) New

Species of Termitomyces (Lyophyllaceae, Basidiomycota) from Sabah (Northern

Borneo), Malaysia. Mycobiology March 202048(9):1-9.

DOI:10.1080/12298093.2020.1738743

●

Lee SS, Watling & Noraini

Sikin. (2002). Ectomycorrhizal basidiomata fruiting in lowland rain forests of

Peninsular Malaysia. Bois et Forêts des

Tropiques 274: 33–43

●

Marek Barta & Ľudovít Cagáň.

(2006). Aphid-pathogenic Entomophthorales (their taxonomy, biology and

ecology). Biologia 61(Suppl 21):S543-S616. DOI:10.2478/s11756-007-0100-x

●

Mohamad Hesam Shahrajabian et. al.

(2017). Chemical compounds and health benefits of Tremella, a valued mushroom

as both cuisine and medicine in ancient China and modern era. Amazonian Journal

of Plant Research 4(3):692-697. DOI:10.26545/ajpr.2020.b00077x

●

Nandris, D.; Nicole, M.; Geiger,

J.P. (1987) Root rot diseases of rubber trees. Plant Dis. 71, 298–306.

●

Patrick Pol. (2024) Spinellus

Fusiger on Mycena: parasites on the forest floor. Take Me North Blog. Oct 29,

2024. URL:https://www.takemenorth.com/blog/spinellus-fusiger/

●

Pegler DN, Vanhaecke M. (1994).

Termitomyces of Southeast Asia. Biology, Environmental Science. Kew Bulletin. DOI:10.2307/4118066.

●

Paul M Kirk & Kerstin Voigt.

(2014). Fungi: Classification of Zygomycetes: Reappraisal as Coherent Class

Based on a Comparison between Traditional versus Molecular Systematics.

Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology, 54–67. DOI:10.1016/B978-0-12-384730-0.00136-1.

●

Samsudin, N. I. P., &

Abdullah, N. (2019). Edible mushrooms from Malaysia: A literature review on

their nutritional and medicinal properties. International Food Research Journal

26(1): 11 – 31.

●

Turnbull E, Watling R. (1999).

Some records of Termitomyces from old world rainforests. Kew Bulletin Vol. 54,

No. 3, pp. 731-738.

●

Sasikala et al. (2023) Formulation

and Development of Tremella Fuciformis Whitening Gel. Current Trends in

Biotechnology and Pharmacy, Vol. 17 No. 4A (Supplement). DOI:

https://doi.org/10.5530/ctbp.2023.4s.94.

●

Sassy Bhawamai and Kwanchanok

Hunthayung (2024). Anti-inflammatory effects of snow mushroom (Tremella

fuciformis) drinks with different types of natural sweeteners on RAW 264.7

macrophages stimulated with lipopolysaccharide. Agriculture and Natural Resources

058(3):295-302. DOI:10.34044/j.anres.2024.58.3.01

●

Siddiquee S, Rovina K, Naher L, et

al. (2015). Phylogenetic relationships of Termitomyces aurantiacus inferred

from internal transcribed spacers DNA sequences. Advances in Bioscience and

Biotechnology, Vol.6 No.5, DOI: 10.4236/abb.2015.65035.

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

Comments

Post a Comment